Inulin-Model.RmdBuilding and evaluation of a PBPK model for inulin in rats

| Version | 1.0-OSP12.3 |

|---|---|

| based on Model Snapshot and Evaluation Plan | https://github.com/Open-Systems-Pharmacology/Inulin-Model/releases/tag/v1.0 |

| OSP Version | 12.3 |

| Qualification Framework Version | 3.2 |

This evaluation report and the corresponding PK-Sim project file are filed at:

https://github.com/Open-Systems-Pharmacology/OSP-PBPK-Model-Library/

Table of Contents

1 Introduction

Inulin is a highly hydrophilic polysaccharide which does not distribute into cells and is cleared via glomerular filtration.

Inulin has a considerably smaller solute radius than the proteins which had been used to develop the generic large molecule physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) model in PK-Sim (Niederalt 2018).

The herein presented evaluation report evaluates the performance of the PBPK model for inulin in rats using the large molecule model in PK-Sim.

The presented inulin PBPK model as well as the respective evaluation plan and evaluation report are provided open-source (https://github.com/Open-Systems-Pharmacology/Inulin-Model).

2 Methods

2.1 Modeling Strategy

The development of the large molecule PBPK model in PK-Sim® has previously been described by Niederalt et al. (Niederalt 2018). In short, the model was built as an extension of the PK-Sim® model for small molecules incorporating (i) the two-pore formalism for drug extravasation from blood plasma to interstitial space, (ii) lymph flow, (iii) endosomal clearance and (iv) protection from endosomal clearance by neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn) mediated recycling.

For model development and evaluation, PK data were used from compounds with a wide range of solute radii and from different species. The PK data used for parameter estimation were from the following compounds: antibody–drug conjugate BAY 79-4620 in mice (Bayer in house data), antibody 7E3 in wild-type and FcRn knockout mice (Garg 2007, Garg2009), domain antibody dAb2 in mice (Sepp 2015), antibodies MEDI-524 and MEDI-524-YTE in monkeys (Dall’Acqua 2006), and antibody CDA1 in humans (Taylor 2008). The PK data used for model evaluation were from inulin in rats (Tsuji1983) and tefibazumab in humans (Reilly 2005).

The PBPK model including the estimated physiological parameters as described by Niederalt et al. (Niederalt 2018) is available in the Open Systems Pharmacology Suite from version 7.1 onwards.

This evaluation report focuses on the PBPK model for inulin.

Details about input data (physicochemical, in vitro and PK) can be found in Section 2.2.

Details about the structural model and its parameters can be found in Section 2.3.

2.2 Data

2.2.1 In vitro / physico-chemical Data

A literature search was performed to collect available information on physicochemical properties of Inulin. The obtained information from literature is summarized in the table below.

| Parameter | Unit | Value | Source | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MW | g/mol | 5000-5500 | Ohno 1978 | Molecular weight |

| r | nm | 1.39 | Ghandehari 1997 | Hydrodynamic solute radius |

| logP | µM | < -10 | Dubbelboer 2022 | Lipophilicity (octanol/water partition coefficient). Inulin is highly hydrophilic. A logP = -10 is insensitively small in the PBPK model. |

| Kd (FcRn) | µM | 999,999 | Dissociation constant for binding to FcRn. High value representing no FcRn binding. |

2.2.2 PK Data

Published plasma and tissue PK data on inulin in rats were used.

| Publication | Description |

|---|---|

| Tsuji 1983 | Plasma and tissue concentrations after i.v. application of 20 and 200 mg/kg inulin in rats (for 200 mg/kg plasma only). |

2.3 Model Parameters and Assumptions

2.3.2 Distribution

The standard vascular properties of the different tissues (hydraulic conductivity, pore radii, fraction of flow via large pores) and standard lymph and fluid recirculation flow rates from PK-Sim were used (Niederalt 2018).

2.3.3 Metabolism and Elimination

Inulin is renally excreted via glomerular filtration. The standard glomerular filtration rate from the PK-Sim library was used (GFR fraction = 1).

2.3.4 Tissue Concentrations

For the comparison with experimental data the parameters

Fraction of blood for sampling used in the Observer for the

tissue concentrations were set for all organs to 0.18. This value is

based on the parameter identification for different compounds reported

in Ref. (Niederalt 2018) for comparison

with tissue dissection data. (The parameter

Fraction of blood for sampling specifies residual blood in

tissue as ratio of blood volume contributing to the measured tissue

concentration to the total in vivo capillary blood volume.)

| Model Parameter | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

Fraction of blood for sampling (all organs) |

0.18 |

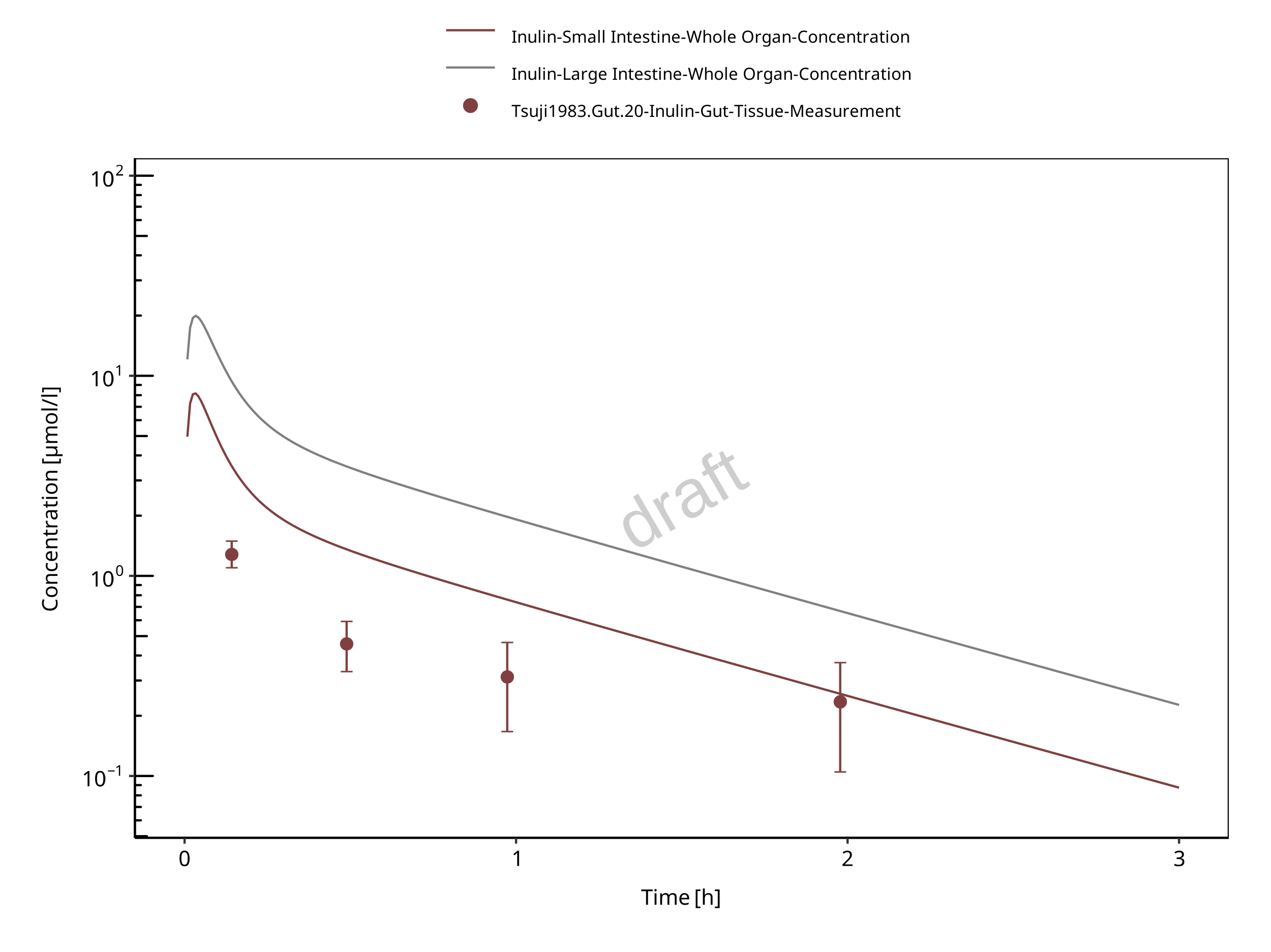

Experimentally, gut concentrations (from duodenum to the cecum) were measured (Tsuji 1983). In the present evaluation report, the experimental gut concentrations were compared to simulated organ concentrations for small and large intestine separately in the goodness of fit plots as well as in the concentration-time profile plot.

3 Results and Discussion

The PBPK model for inulin was evaluated with plasma and tissue PK data from rats.

The next sections show:

- the final model parameters for the building blocks: Section 3.1.

- the overall goodness of fit: Section 3.2.

- simulated vs. observed concentration-time profiles for the clinical studies used for model building and for model verification: Section 3.3.

3.1 Final input parameters

The compound parameter values of the final PBPK model are illustrated below.

Compound: Inulin

Parameters

| Name | Value | Value Origin | Alternative | Default |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solubility at reference pH | 9999 mg/l | Other-/Dummy value not used in the simulation | Measurement | True |

| Reference pH | 7 | Other-/Dummy value not used in the simulation | Measurement | True |

| Lipophilicity | -10 Log Units | Other-Highly hydrophilic | Measurement | True |

| Fraction unbound (plasma, reference value) | 1 | Other-Assumption | Measurement | True |

| Is small molecule | Yes | |||

| Molecular weight | 5500 g/mol | Publication-Ohno1978 | ||

| Plasma protein binding partner | Unknown | |||

| Radius (solute) | 0.00139 µm | Publication-Ghandehari1997 |

3.2 Diagnostics Plots

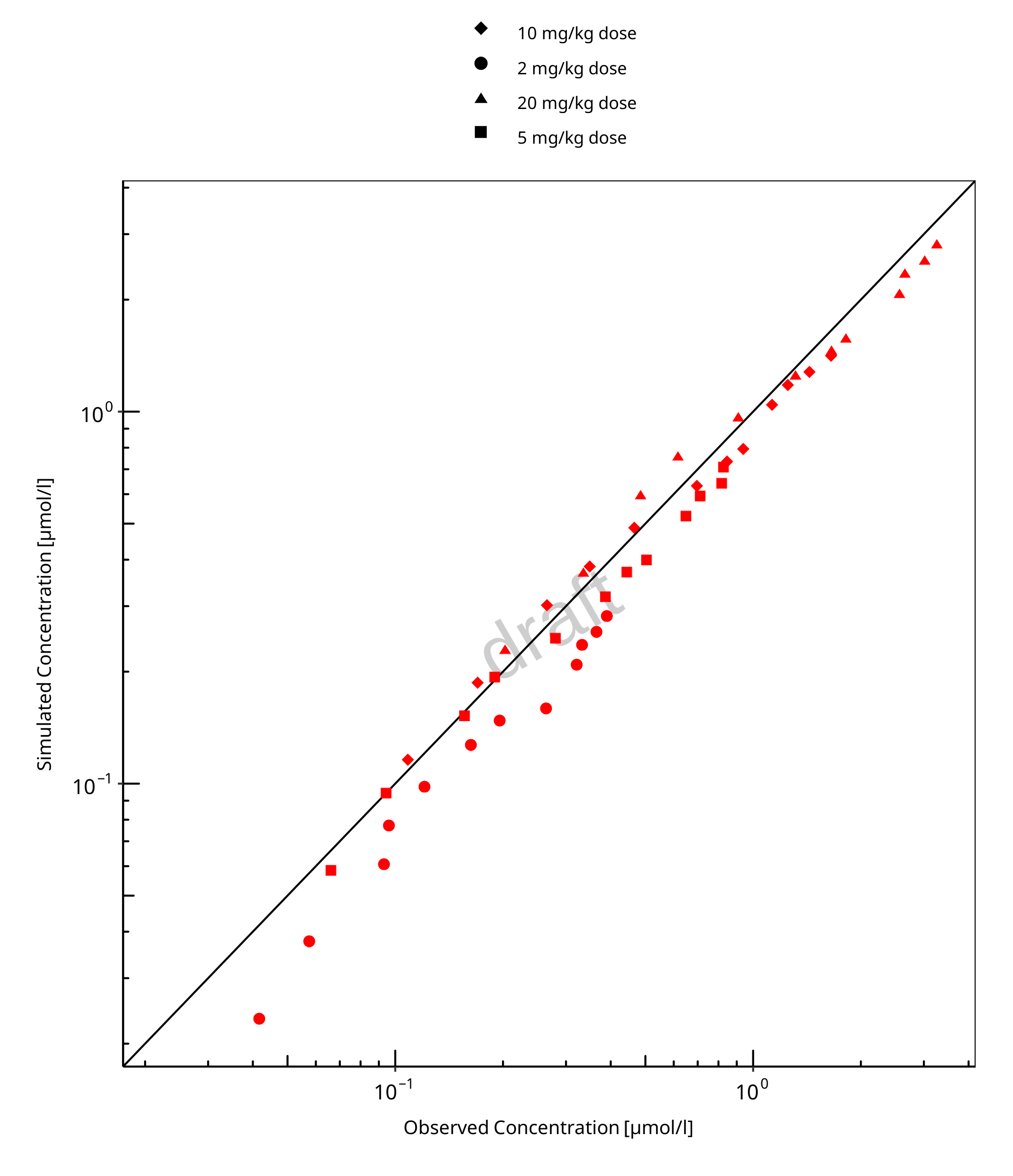

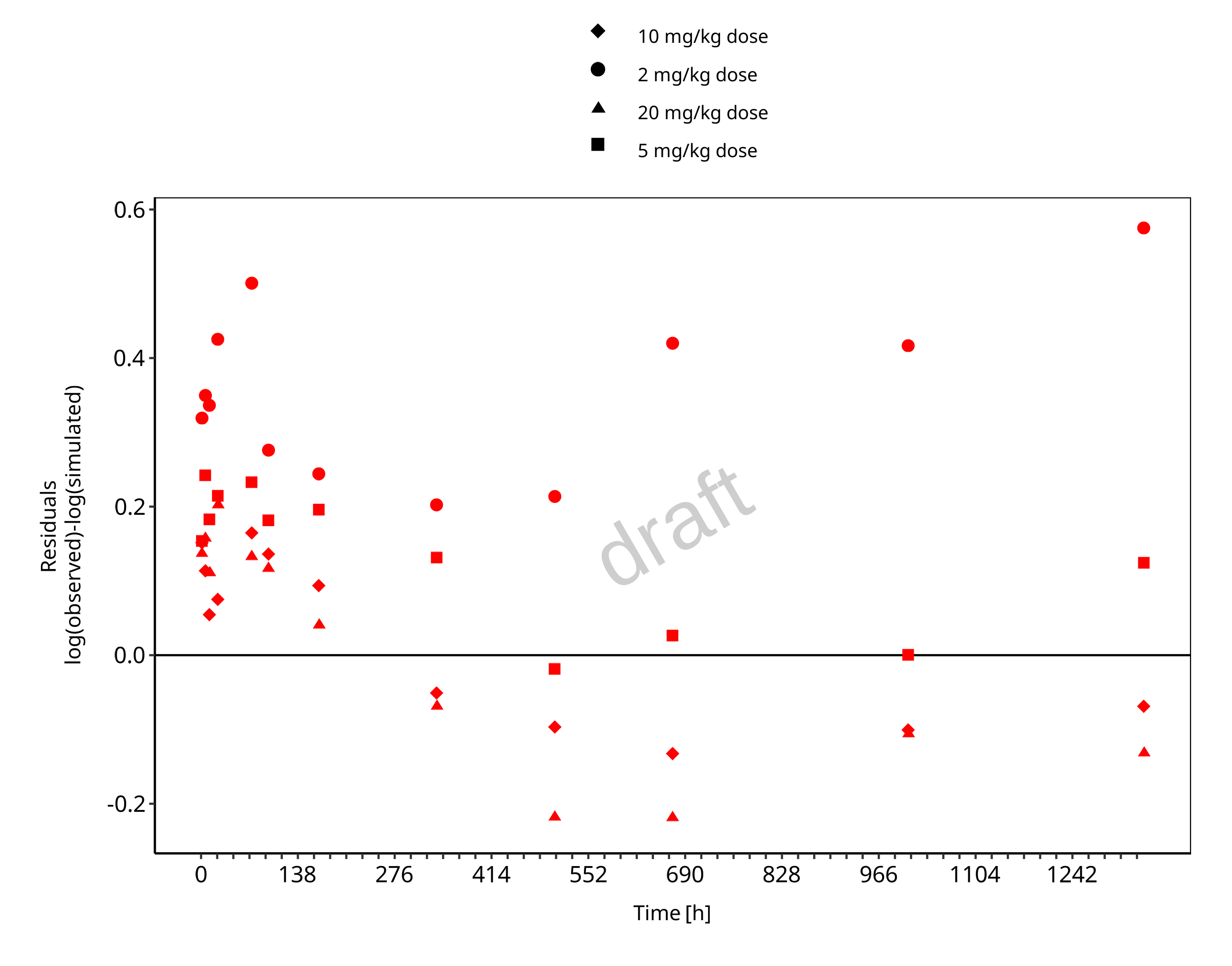

Below you find the goodness-of-fit visual diagnostic plots for the PBPK model performance of all data used presented in Section 2.2.2.

The first plot shows observed versus simulated plasma concentration, the second weighted residuals versus time.

Table 3-1: GMFE for Goodness of fit plot for concentration in plasma and tissues

| Group | GMFE |

|---|---|

| Plasma concentrations (20 & 200 mg/kg dose) | 1.38 |

| Tissue concentrations (20 mg/kg dose) | 2.01 |

| All | 1.71 |

Figure 3-1: Goodness of fit plot for concentration in plasma and tissues

Figure 3-2: Goodness of fit plot for concentration in plasma and tissues

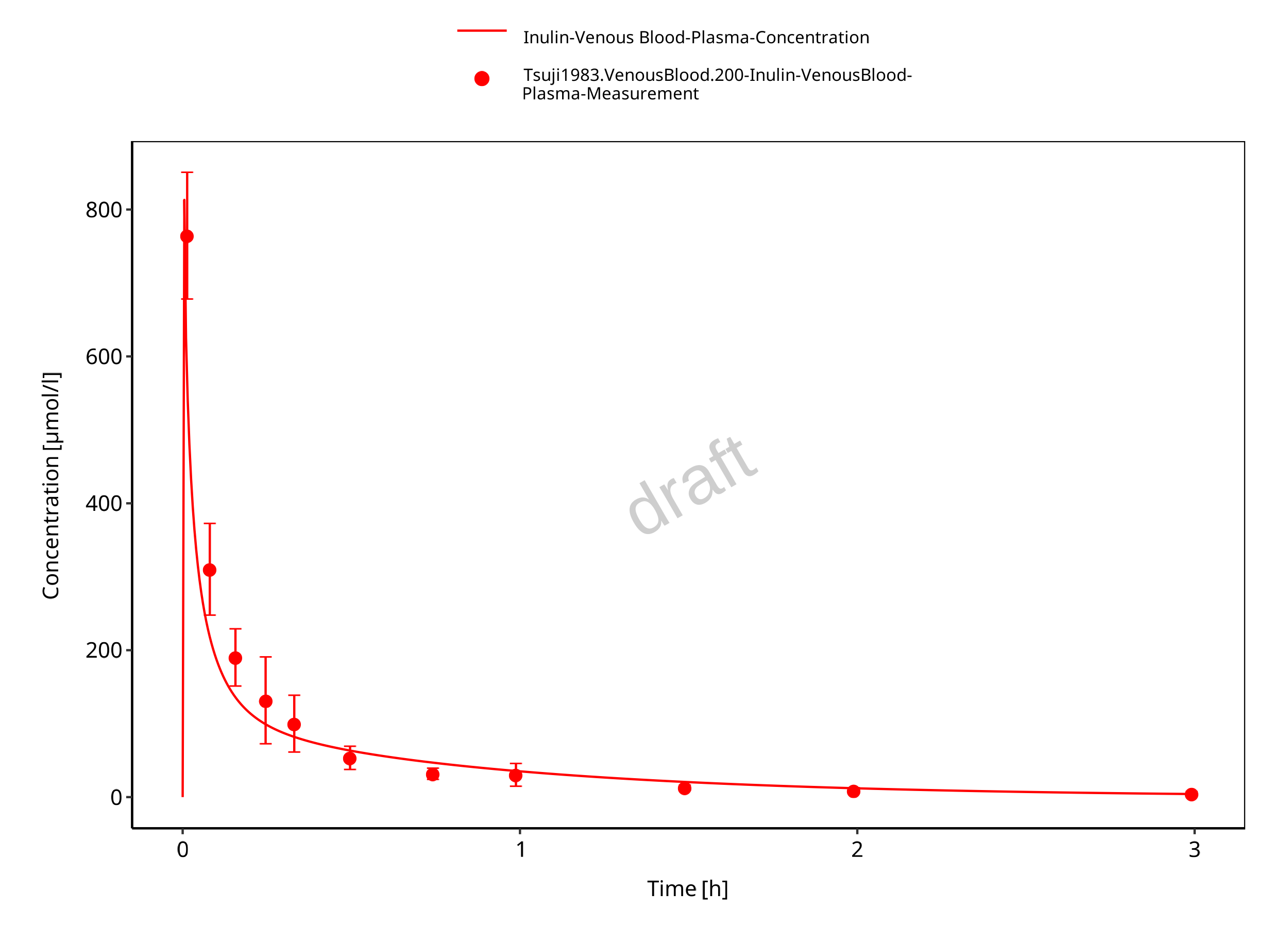

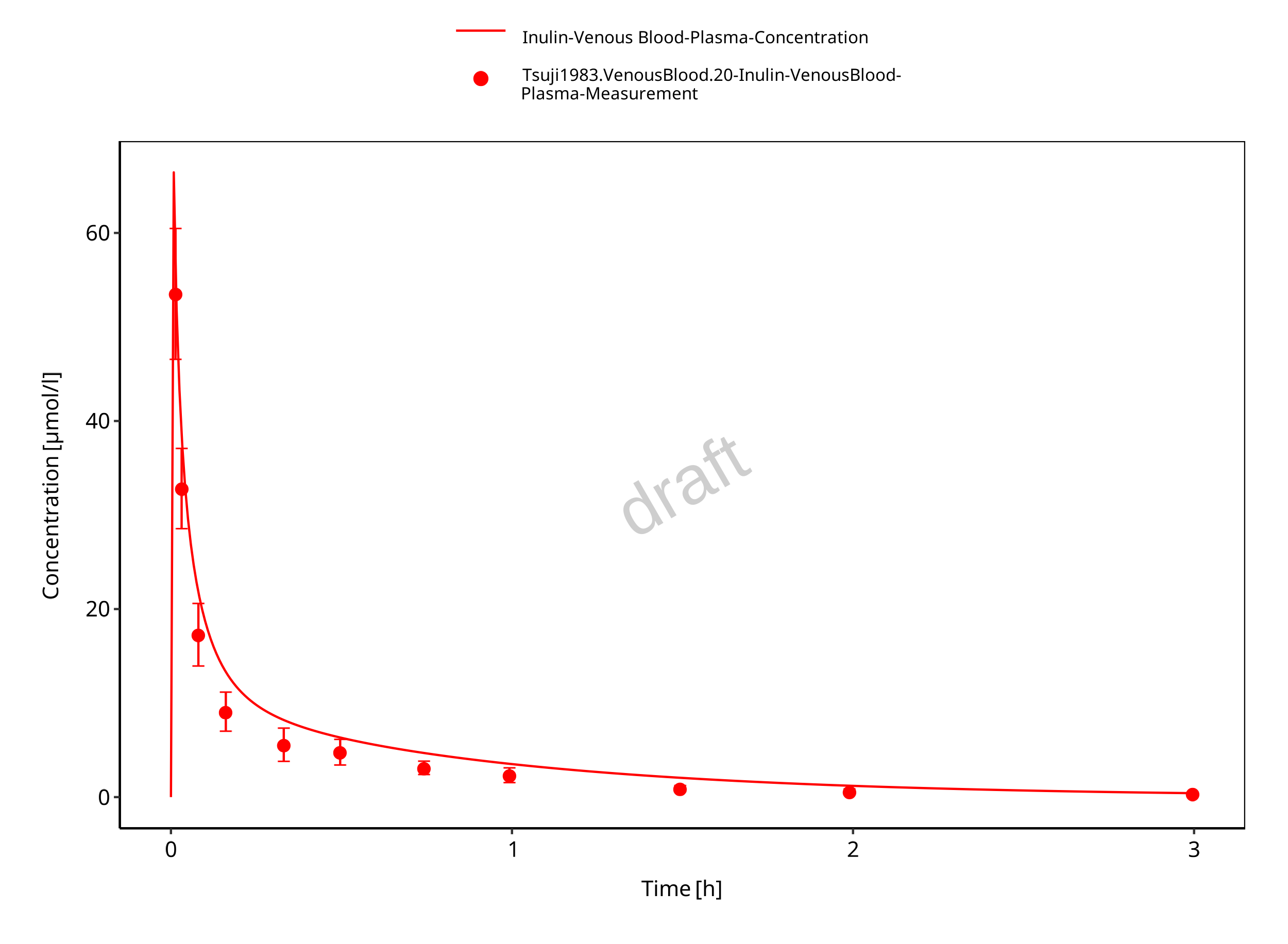

3.3 Concentration-Time Profiles

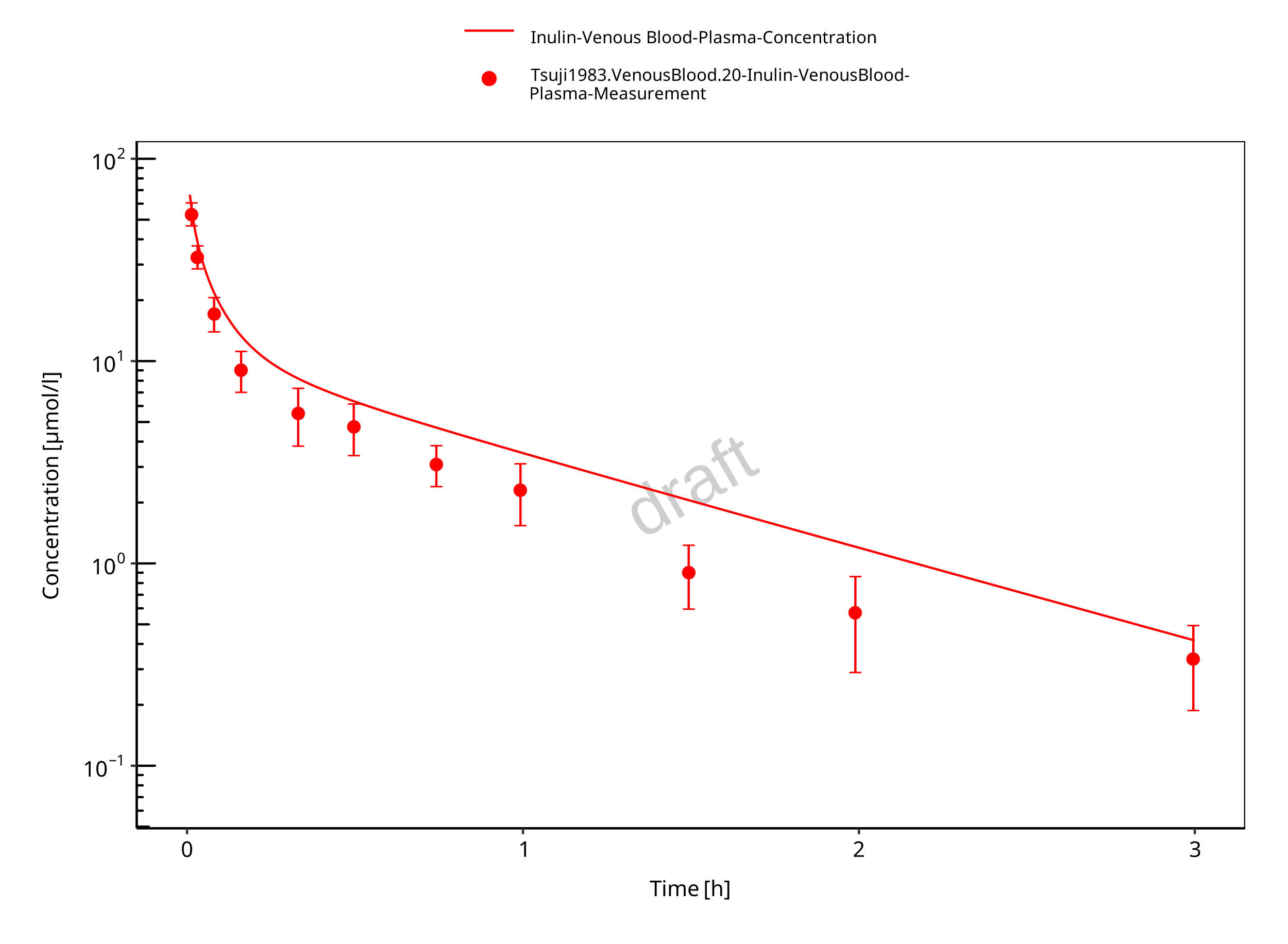

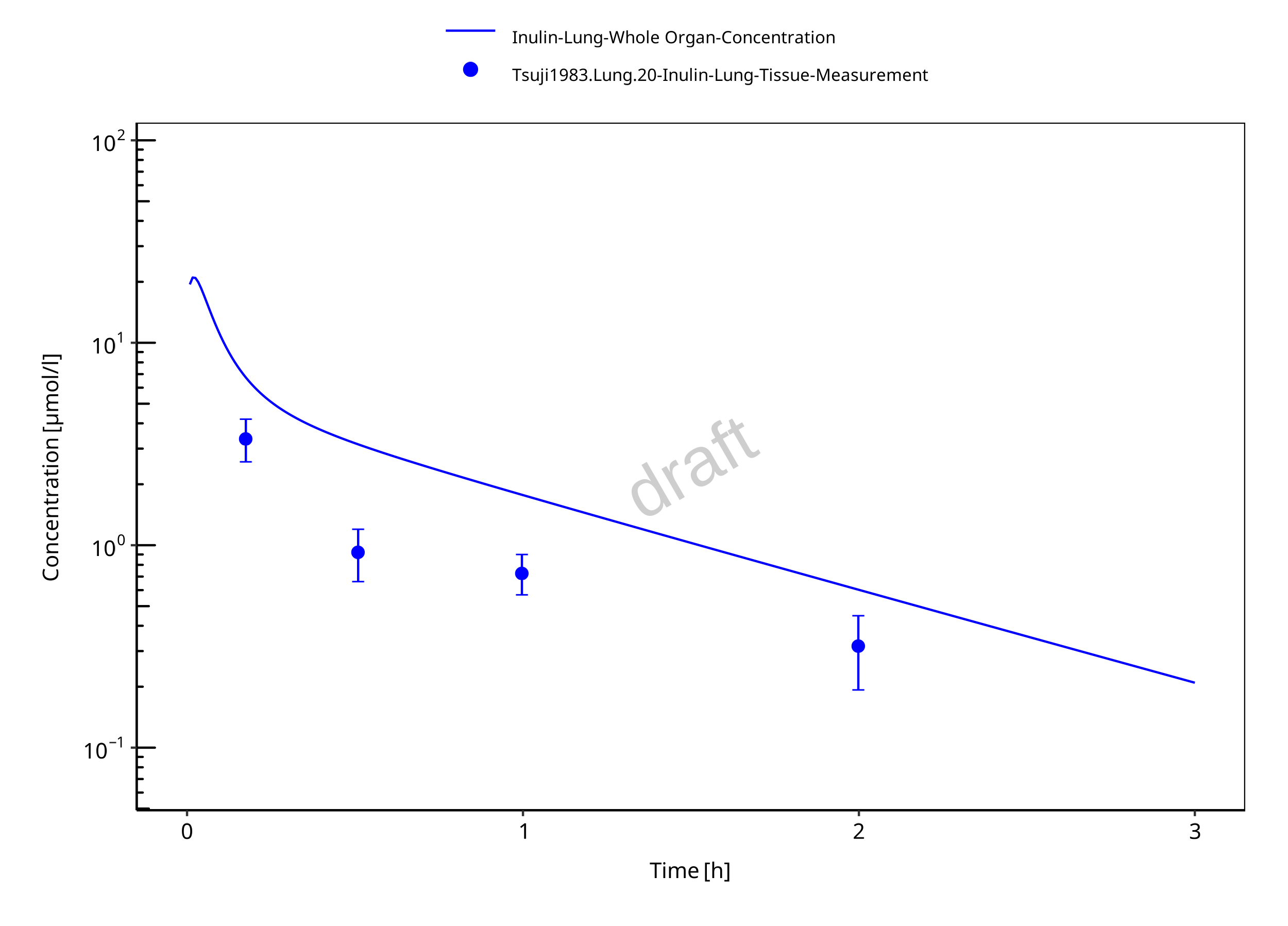

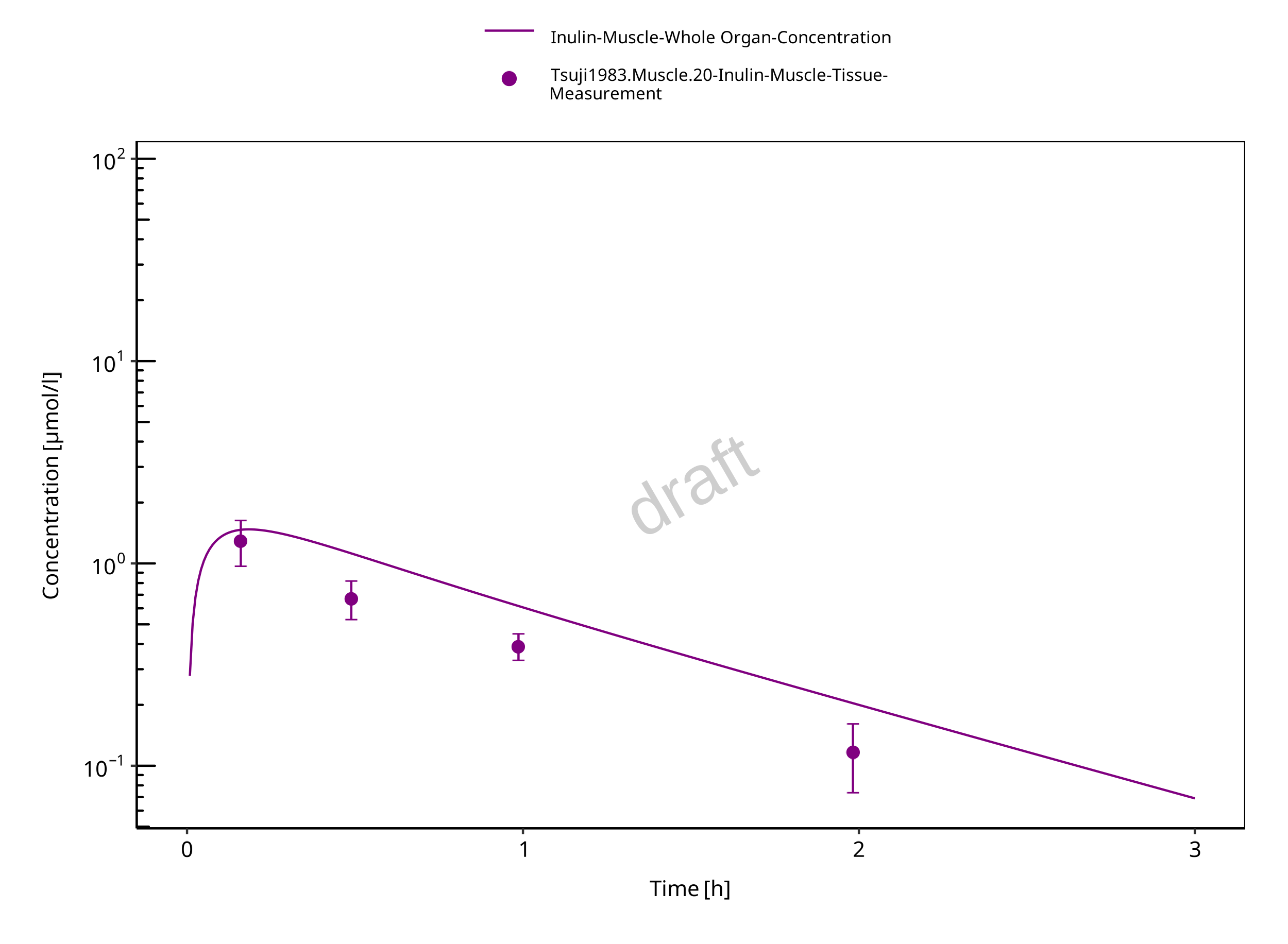

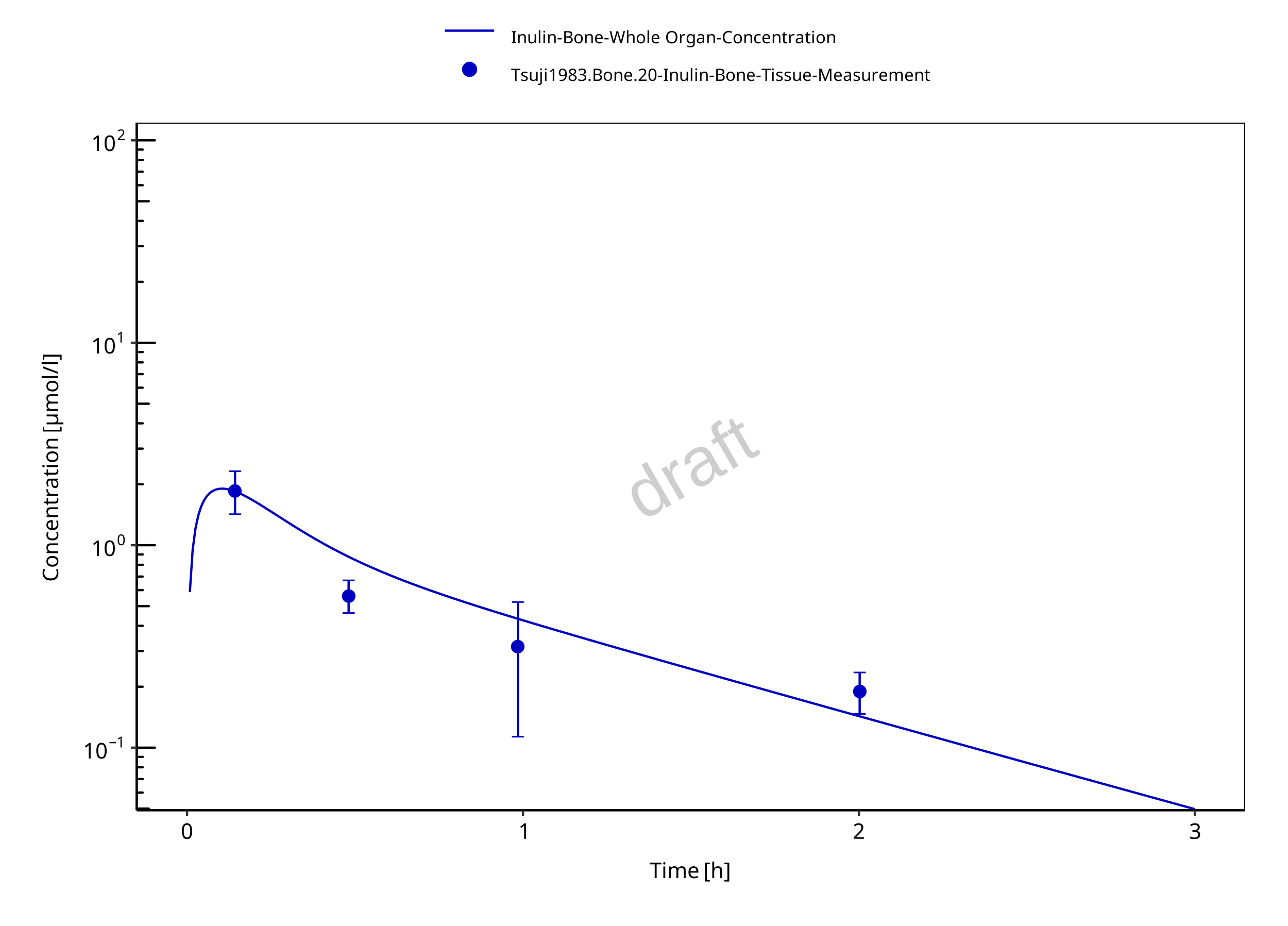

Simulated versus observed concentration-time profiles of all data listed in Section 2.2.2 are presented below.

Figure 3-3: Plasma concentration (linear scale)

Figure 3-4: Plasma concentration (log scale)

Figure 3-5: Plasma (linear scale)

Figure 3-6: Plasma (log scale)

Figure 3-7: Lung

Figure 3-8: Muscle

Figure 3-9: Bone

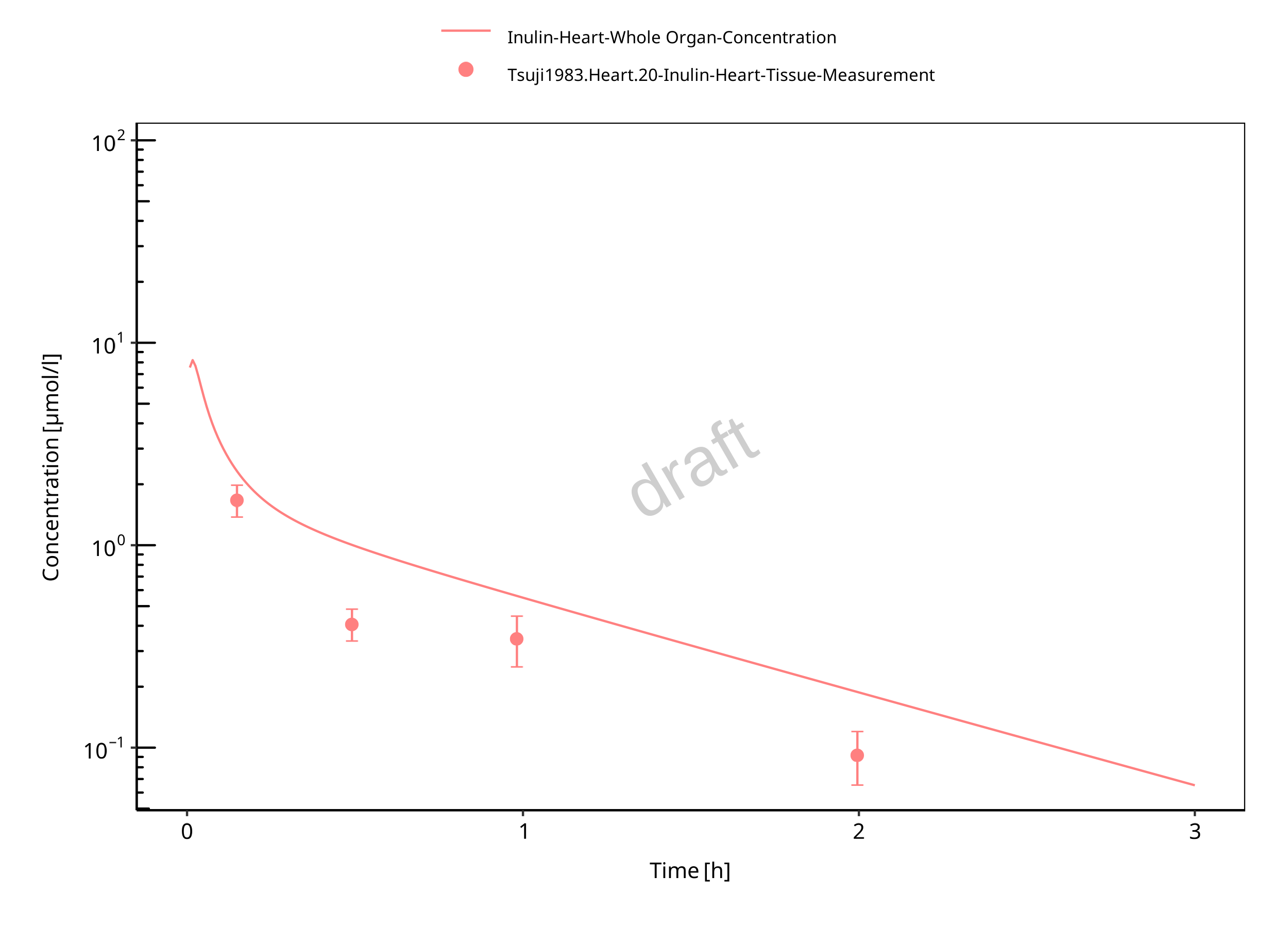

Figure 3-10: Heart

Figure 3-11: Skin

Figure 3-12: Gut

4 Conclusion

The herein presented PBPK model overall adequately describes the plasma pharmacokinetics of inulin in rats. Tissue concentrations tend to be overestimated by the model, the largest deviations being observed for lung, gut, and heart concentrations. Simulations are predictions without adjusting any compound specific parameter (i.e., using a literature value for the solute radius of inulin and the default physiological parameters in PK-Sim especially for the glomerular filtration rate, vascular properties and compartment volumes).

5 References

Dall’Acqua 2006 Dall’Acqua WF, Kiener PA, Wu H. Properties of human IgG1s engineered for enhanced binding to the neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn). J Biol Chem. 2006 Aug; 281(33):23514-23524. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604292200.

Dubbelboer 2022 Dubbelboer, I. R., Sjögren, E. Overview of authorized drug products for subcutaneous administration: Pharmaceutical, therapeutic, and physicochemical properties. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2022 Jun; 173:106181. doi.org/10.1016/j.ejps.2022.106181.

Garg 2007 Garg A, Balthasar JP. Physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) model to predict IgG tissue kinetics in wild-type and FcRn-knockout mice. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn. 2007 Jul; 34(5):687-709. doi: 10.1007/s10928-007-9065-1.

Garg 2009 Garg A, Balthasar J. Investigation of the influence of FcRn on the distribution of IgG to the brain. AAPS J. 2009 July; 11(3):553-557. doi: 10.1208/s12248-009-9129-9.

Ghandehari 1997 Ghandehari H, Smith PL, Ellens H, Yeh PY, Kopecek J. Size-dependent permeability of hydrophilic probes across rabbit colonic epithelium. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997 Feb; 280(2):747-753.

Lobo 2004 Lobo ED, Hansen R J, Balthasar JP. Antibody pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. J Pharm Sci. 2004 Nov;93(11):2645-2668. doi: 10.1002/jps.20178.

Niederalt 2018 Niederalt C, Kuepfer L, Solodenko J, Eissing T, Siegmund HU, Block M, Willmann S, Lippert J. A generic whole body physiologically based pharmacokinetic model for therapeutic proteins in PK-Sim. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn. 2018 Apr;45(2):235-257. doi: 10.1007/s10928-017-9559-4.

Ohno 1978 Ohno K, Pettigrew KD, Rapoport SI. Lower limits of cerebrovascular permeability to nonelectrolytes in the conscious rat. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 1978 Sep;235(3):H299-H307. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1978.235.3.H299.

Reilly 2005 Reilley S, Wenzel E, Reynolds L, Bennett B, Patti JM, Hetherington S. Open-label, dose escalation study of the safety and pharmacokinetic profile of tefibazumab in healthy volunteers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005 Mar;49(3):959–962. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.3.959-962.2005.

Sepp 2015 Sepp A, Berges A, Sanderson A, Meno-Tetang G. Development of a physiologically based pharmacokinetic model for a domain antibody in mice using the two-pore theory. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn. 2015 Jan;42(2):97-109. doi: 10.1007/s10928-014-9402-0.

Taylor 1984 Taylor AE, Granger DN. Exchange of macromolecules across the microcirculation. Handbook of Physiology - Cardiovascular System. Microcirculation (Eds. Renkin EM and Michel CC. Bethesda, MD, American Physiological Society). 1984; Vol. 4(Pt 2):467–520.

Taylor 2008 Taylor CP, Tummala S, Molrine D, Davidson L, Farrell RJ, Lembo A, Hibberd PL, Lowy I, Kelly CP. Open-label, dose escalation phase I study in healthy volunteers to evaluate the safety and pharmacokinetics of a human monoclonal antibody to Clostridium difficile toxin A. Vaccine. 2008 Jun;26(27-28):3404–3409. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.04.042.

Tsuji 1983 Tsuji A, Yoshikawa T, Nishide K, Minami H, Kimura M, Nakashima E, Terasaki T, Miyamoto E, Nightingale CH, Yamana T. Physiologically based pharmacokinetic model for beta-lactam antibiotics I: tissue distribution and elimination in rats. J Pharm Sci. 1983 Nov;72(11):1239-1252. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600721103.