BAY794620-Model.RmdBuilding and evaluation of a PBPK model for BAY 79-4620 in mice

| Version | 1.0-OSP11.0 |

|---|---|

| based on Model Snapshot and Evaluation Plan | https://github.com/Open-Systems-Pharmacology/BAY794620-Model/releases/tag/v1.0 |

| OSP Version | 11.0 |

| Qualification Framework Version | 3.0 |

This evaluation report and the corresponding PK-Sim project file are filed at:

https://github.com/Open-Systems-Pharmacology/OSP-PBPK-Model-Library/

1 Introduction

BAY 79-4620 is an antibody–drug conjugate consisting of a human IgG1 mAb directed against human carbonic anhydrase IX (CA IX) conjugated to the toxophore monomethylauristatin E (MMAE) via a valine-citrulline based linker (Petrul 2012).

For BAY 79-4620, tissue concentration-time profiles for a large number of different mice tissues were measured and used together with pharmacokinetic (PK) data from 5 other compounds to identify unknown parameters during the development of the generic large molecule physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) model in PK-Sim (Niederalt 2018).

The herein presented evaluation report evaluates the performance of a PBPK model for BAY 79-4620 in xenograft mice for the PK data used for the development of the generic large molecule model in PK-Sim. A standard PK-Sim model was used without an additional tumor organ and without target mediated drug disposition effects from CA IX binding in the tumor - in contrast to the model which has been used in Ref. (Niederalt 2018).

The presented BAY 79-4620 PBPK model as well as the respective evaluation plan and evaluation report are provided open-source (https://github.com/Open-Systems-Pharmacology/BAY794620-Model).

2 Methods

2.1 Modeling Strategy

The development of the large molecule PBPK model in PK-Sim® has previously been described by Niederalt et al. (Niederalt 2018). In short, the model was built as an extension of the PK-Sim® model for small molecules incorporating (i) the two-pore formalism for drug extravasation from blood plasma to interstitial space, (ii) lymph flow, (iii) endosomal clearance and (iv) protection from endosomal clearance by neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn) mediated recycling.

For model development and evaluation, PK data were used from compounds with a wide range of solute radii and from different species. The PK data used for parameter estimation were from the following compounds: antibody–drug conjugate BAY 79-4620 in mice (Bayer in house data), antibody 7E3 in wild-type and FcRn knockout mice (Garg 2007, Garg2009), domain antibody dAb2 in mice (Sepp 2015), antibodies MEDI-524 and MEDI-524-YTE in monkeys (Dall’Acqua 2006), and antibody CDA1 in humans (Taylor 2008). The PK data used for model evaluation were from inulin in rats (Tsuji1983) and tefibazumab in humans (Reilly 2005).

The PBPK model including the estimated physiological parameters as described by Niederalt et al. (Niederalt 2018) is available in the Open Systems Pharmacology Suite from version 7.1 onwards.

This evaluation report focuses on the PBPK model for the antibody–drug conjugate BAY 79-4620.

Details about input data (physicochemical, in vitro and PK) can be found in Section 2.2.

Details about the structural model and its parameters can be found in Section 2.3.

2.2 Data

2.2.1 In vitro / physico-chemical Data

A literature search was performed to collect available information on physicochemical properties of BAY 79-4620. The obtained information from literature is summarized in the table below.

| Parameter | Unit | Value | Source | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MW | g/mol | 152000 | Bayer in-house data | Molecular weight |

| r | nm | 5.34 | Taylor 1984 | Hydrodynamic solute radius |

| Kd (FcRn) | µM | 0.082 | Zhou 2003 | Dissociation constant for binding of a humane IgG1 antibody to murine FcRn at pH 6 |

2.2.2 PK Data

The biodistribution data from mice for BAY 79-4620 were Bayer AG in house data taken from two studies:

| Data | Description |

|---|---|

| Whole-body autoradiography | Female nude mice (NMRI nu/nu), bearing HT-29 human colon carcinoma xenografts, were dosed intravenously with 1.25 mg/kg body weight of 125I-labeled BAY 79-4620. The distribution of total radioactivity in organs and tissues was determined by quantitative whole-body autoradiography after sacrificing the mice (two per time) at various time points after administration. |

| Wet-tissue dissection study | Female nude mice (NMRI nu/nu), bearing HT-29 human colon carcinoma xenografts, were dosed intravenously with 2 µCi (approx. 500 ng) of 125I-labeled BAY 79-4620. The distribution of total radioactivity in organs and tissues was determined after sacrificing the mice (three per time) and dissection of the organs at various time points after administration by determination of radioactivity using a gamma-counter. The concentrations were reported as percentage of dose / g tissue. These values were converted to concentrations in ng/ml assuming a density of 1 g/ml for all tissues except for bone for which a density of 1.5 g/ml was assumed (as in Ref. Baxter 1994). |

2.3 Model Parameters and Assumptions

2.3.2 Distribution

The standard lymph and fluid recirculation flow rates and the standard vascular properties of the different tissues (hydraulic conductivity, pore radii, fraction of flow via large pores) from PK-Sim were used. BAY 79-4620, among other compounds, has been used to identify these lymph and fluid recirculation flow rates used in PK-Sim (Niederalt 2018).

A standard PK-Sim model was used without an additional tumor organ - in contrast to the model which has been used in Ref. (Niederalt 2018). It was assumed that BAY 79-4620 is not cross-reactive to murine CA IX, i.e. there is no drug-target binding due to the neglect of tumor tissue in the present PK-Sim standard model (again in contrast to the model used in Ref. (Niederalt 2018)).

2.3.3 Metabolism and Elimination

The FcRn mediated clearance present in the standard PK-Sim model was used as only clearance process (in contrast to the model used in Ref. (Niederalt 2018), where there is an additional target mediated clearance process in tumor tissue). The affinity to FcRn in the endosomal space was fitted to the PK data. The same value as fitted in Ref. (Niederalt 2018) was used since the contribution from target mediated clearance was small.

2.3.4 Tissue Concentrations

For the comparison with experimental data the parameters

Fraction of blood for sampling used in the Observer for the

tissue concentrations were set for all organs to 0.18 for comparison

with tissue dissection data and to 0.42 for comparison with

autoradiography data according to the fit results (across compounds) in

Ref. (Niederalt 2018). (The parameter

Fraction of blood for sampling specifies residual blood in

tissue as ratio of blood volume contributing to the measured tissue

concentration to the total in vivo capillary blood volume.)

In the present evaluation report, the experimental intestine concentrations from the tissue dissection study were compared to simulated organ concentrations for small and large intestine separately in the goodness of fit plots as well as in the concentration-time profile plot.

2.3.5 Automated Parameter Identification

The table shows the parameter values that were specified in the model based on the parameter identification reported in Ref. (Niederalt 2018), and which were not included in the PK-Sim database since version 7.1.

| Model Parameter | Optimized Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

Kd(FcRn) in endosomal space |

12.7 | µmol/L |

Fraction of blood for sampling (all organs) - for

comparison with tissue dissection data |

0.18 | |

Fraction of blood for sampling (all organs) - for

comparison with autoradiography data |

0.42 |

3 Results and Discussion

The PBPK model for BAY 79-4620 was evaluated with blood and tissue PK data from mice.

These PK data have been used together with PK data from 5 other compounds to simultaneously identify parameters during the development of the generic model for proteins and large molecules in PK-Sim (Niederalt 2018).

The fitted dissociation constant for binding to FcRn in the endosomal space is rather high compared to usual dissociation constants. This might reflect a lowered affinity to FcRn due to the conjugation of the toxophore or alternatively is a surrogate for a clearance process not represented in the model.

The next sections show:

- the final model parameters for the building blocks: Section 3.1.

- the overall goodness of fit: Section 3.2.

- simulated vs. observed concentration-time profiles for the clinical studies used for model building and for model verification: Section 3.3.

3.1 Final input parameters

The compound parameter values of the final PBPK model are illustrated below.

Compound: BAY794620

Parameters

| Name | Value | Value Origin | Alternative | Default |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solubility at reference pH | 99999 mg/l | Other-/Dummy value not used in the simulation | Measurement | True |

| Reference pH | 7 | Other-/Dummy value not used in the simulation | Measurement | True |

| Lipophilicity | -5 Log Units | Other-/Dummy value not used in the simulation | Measurement | True |

| Fraction unbound (plasma, reference value) | 1 | Other-Assumption | Measurement | True |

| Is small molecule | No | |||

| Molecular weight | 152000 g/mol | |||

| Plasma protein binding partner | Unknown | |||

| Radius (solute) | 0.00534 µm | Publication-Taylor1984 | ||

| Kd (FcRn) in endosomal space | 12.7 µmol/l | Parameter Identification |

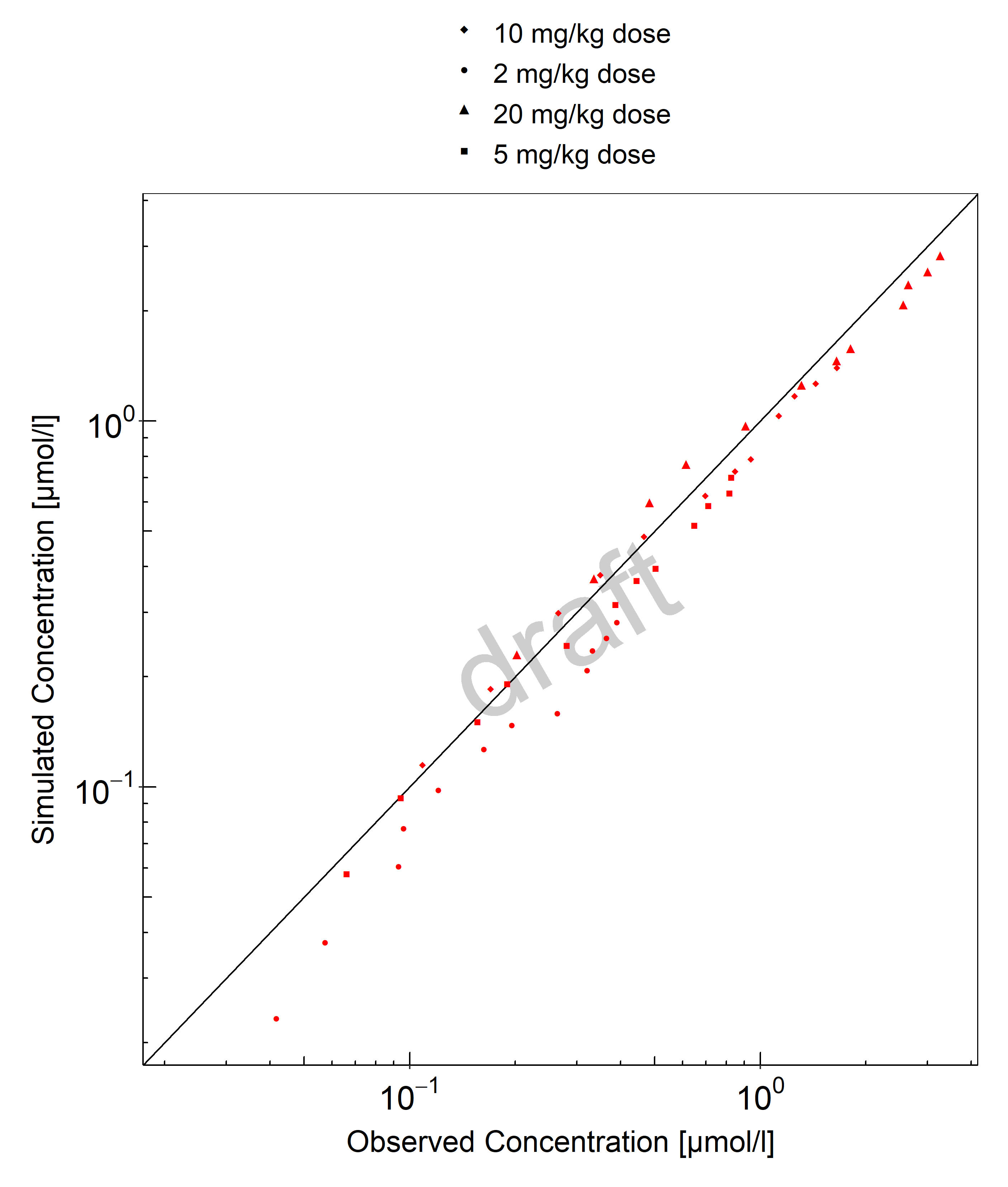

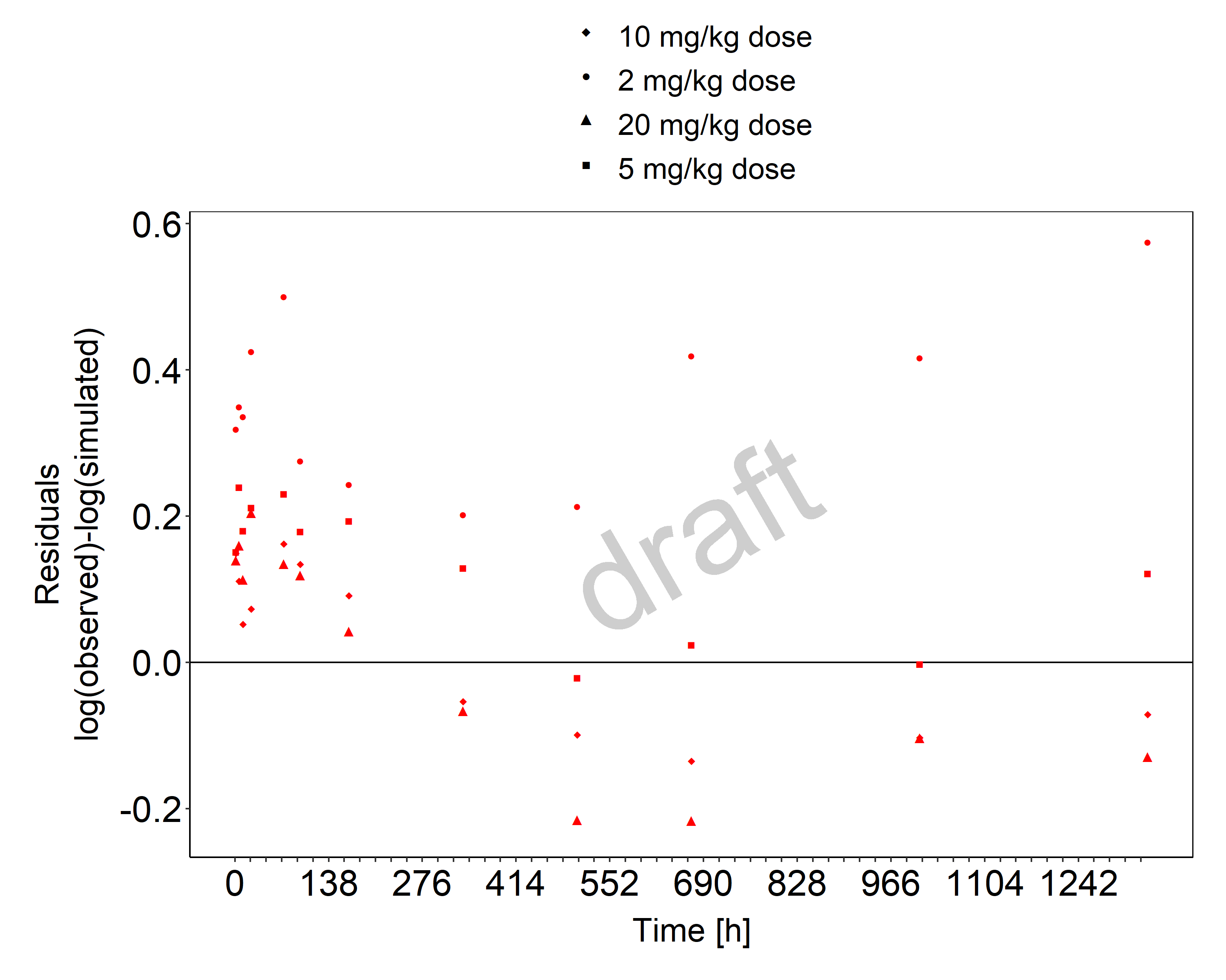

3.2 Diagnostics Plots

Below you find the goodness-of-fit visual diagnostic plots for the PBPK model performance of all data used presented in Section 2.2.2.

The first plot shows observed versus simulated plasma concentration, the second weighted residuals versus time.

Table 3-1: GMFE for Goodness of fit plot for concentration in blood and tissues

| Group | GMFE |

|---|---|

| BAY 79-4620 - autoradiography | 1.48 |

| BAY 79-4620 - tissue dissection | 1.62 |

| All | 1.53 |

Figure 3-1: Goodness of fit plot for concentration in blood and tissues

Figure 3-2: Goodness of fit plot for concentration in blood and tissues

3.3 Concentration-Time Profiles

Simulated versus observed concentration-time profiles of all data listed in Section 2.2.2 are presented below.

Figure 3-3: Blood - lin scale

Figure 3-4: Blood - log scale

Figure 3-5: Lung

Figure 3-6: Kidney

Figure 3-7: Skin

Figure 3-8: Muscle

Figure 3-9: Spleen

Figure 3-10: Liver

Figure 3-11: Heart

Figure 3-12: Fat

Figure 3-13: Brain

Figure 3-14: Stomach

Figure 3-15: Pancreas

Figure 3-16: Small Intestine

Figure 3-17: Ovaries

Figure 3-18: Blood - lin scale

Figure 3-19: Blood - log scale

Figure 3-20: Lung

Figure 3-21: Kidney

Figure 3-22: Bone

Figure 3-23: Muscle

Figure 3-24: Spleen

Figure 3-25: Liver

Figure 3-26: Heart

Figure 3-27: Fat

Figure 3-28: Brain

Figure 3-29: Stomach

Figure 3-30: Pancreas

Figure 3-31: Intestine

Figure 3-32: Ovaries

4 Conclusion

The herein presented PBPK model overall adequately describes the pharmacokinetics of BAY 79-4620 in mice. The tissue concentrations from the low dose tissue dissection study (dose approximately 0.025 mg/kg) are similarly well described as the tissue concentrations from the autoradiography study (dose 1.25 mg/kg), with the exception of the late concentrations at 168 h after administration from the tissue dissection study which are underestimated by the model. The largest deviations between measured and simulated concentration-time profiles are observed for spleen concentrations which are overestimated by the model and brain concentrations which are underestimated.

The PK data had been used during the development of the generic large molecule PBPK model in PK-Sim (Niederalt 2018) together with PK data from 5 other compounds (7E3, CDA1, dAb2, MEDI-524 & MEDI-524-YTE).

5 References

Baxter 1994 Baxter LT, Zhu H, Mackensen DG, Jain RK. Physiologically based pharmacokinetic model for specific and nonspecific monoclonal antibodies and fragments in normal tissues and human tumor xenografts in nude mice. Cancer research. 1994 Mar; 54(6):1517-1528.

Dall’Acqua 2006 Dall’Acqua WF, Kiener PA, Wu H. Properties of human IgG1s engineered for enhanced binding to the neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn). J Biol Chem. 2006 Aug; 281(33):23514-23524. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604292200.

Garg 2007 Garg A, Balthasar JP. Physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) model to predict IgG tissue kinetics in wild-type and FcRn-knockout mice. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn. 2007 Jul; 34(5):687-709. doi: 10.1007/s10928-007-9065-1.

Garg 2009 Garg A, Balthasar J. Investigation of the influence of FcRn on the distribution of IgG to the brain. AAPS J. 2009 July; 11(3):553-557. doi: 10.1208/s12248-009-9129-9.

Lobo 2004 Lobo ED, Hansen R J, Balthasar JP. Antibody pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. J Pharm Sci. 2004 Nov;93(11):2645-2668. doi: 10.1002/jps.20178.

Niederalt 2018 Niederalt C, Kuepfer L, Solodenko J, Eissing T, Siegmund HU, Block M, Willmann S, Lippert J. A generic whole body physiologically based pharmacokinetic model for therapeutic proteins in PK-Sim. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn. 2018 Apr;45(2):235-257. doi: 10.1007/s10928-017-9559-4.

Petrul 2012 Petrul HM, Schatz CA, Kopitz CC, Adnane L, McCabe TJ, Trail P, Ha S, Chang YS, Voznesensky A, Ranges G, Tamburini PP. Therapeutic mechanism and efficacy of the antibody–drug conjugate BAY 79-4620 targeting human carbonic anhydrase 9. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 2012 Feb;11(2):340-349. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0523.

Reilly 2005 Reilley S, Wenzel E, Reynolds L, Bennett B, Patti JM, Hetherington S. Open-label, dose escalation study of the safety and pharmacokinetic profile of tefibazumab in healthy volunteers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005 Mar;49(3):959–962. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.3.959-962.2005.

Sepp 2015 Sepp A, Berges A, Sanderson A, Meno-Tetang G. Development of a physiologically based pharmacokinetic model for a domain antibody in mice using the two-pore theory. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn. 2015 Jan;42(2):97-109. doi: 10.1007/s10928-014-9402-0.

Taylor 1984 Taylor AE, Granger DN. Exchange of macromolecules across the microcirculation. Handbook of Physiology - Cardiovascular System. Microcirculation (Eds. Renkin EM and Michel CC. Bethesda, MD, American Physiological Society). 1984; Vol. 4(Pt 2):467–520.

Taylor 2008 Taylor CP, Tummala S, Molrine D, Davidson L, Farrell RJ, Lembo A, Hibberd PL, Lowy I, Kelly CP. Open-label, dose escalation phase I study in healthy volunteers to evaluate the safety and pharmacokinetics of a human monoclonal antibody to Clostridium difficile toxin A. Vaccine. 2008 Jun;26(27-28):3404–3409. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.04.042.

Tsuji 1983 Tsuji A, Yoshikawa T, Nishide K, Minami H, Kimura M, Nakashima E, Terasaki T, Miyamoto E, Nightingale CH, Yamana T. Physiologically based pharmacokinetic model for beta-lactam antibiotics I: tissue distribution and elimination in rats. J Pharm Sci. 1983 Nov;72(11):1239-1252. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600721103.

Zhou 2003 Zhou J, Johnson JE, Ghetie V, Ober RJ, Ward ES. Generation of mutated variants of the human form of the MHC class I-related receptor, FcRn, with increased affinity for mouse immunoglobulin G. J Mol Biol. 2003 Sep;332(4):901-913. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00952-5.